The Royal Prussian 5th Foot Guard Regiment

by Dr Martin Lezius.

"we must not rest from keeping alive the martial ethos in all Germans, young or old, by the memory of our old, glorious armed forces.We must at all times awaken and strengthen understanding, particularly in our upcoming generation, of the merits and tremendous accomplishments of our

Army and Navy, of the history, organization and uniforms of the units."

-Dr Martin Lezius

Pre-War Regiment

(1897-1914)

The 5th Foot Guard Regiment was one of the youngest units in the Guard Corps. It was formed in 31.3.1897, initially only two battalions strong, from the so-called fourth half-battalions of the 3rd Foot Guard Regiment, the Guard Fusilier Regiment, Queen Elisabeth’s and Queen Augusta’s Regiments. The 1st Battalion was initially based in Potsdam, although six months later it would join the 2nd Battalion in Spandau, where the regiment was garrisoned until the outbreak of the Great War.

The uniform of the regiment was similar to that of the 1st Foot Guard Regiment, with white shoulder boards, silver buttons and matching fittings on the helmet (Pickelhaube), but with helmet chin scales of yellow brass. The so-called “old Prussian” pointed white Litzen (braid) were worn on both sides of the collar. Like the Guard Grenadier regiments, the regiment had the distinction of Brandenburg cuffs of the same colour as the tunic. The cuffs were also decorated with the same type of Litzen, three on each cuff. The regiment’s officers wore silver Frederickian-style Stickerei (embroidery) on their collars and cuffs. Their shoulder boards, unlike those of the 1st Foot Guard Regiment’s officers, had a white cloth backing, rather than one of Silbertresse (silver braid) like the Potsdam regiment.

The Regimental Colours of the 5th Guard Regiment were white. The middle field bearing the crowned eagle holding a sword and lightning bolts in its talons, and the quarter medallions with the crowned cypher, were of silver material. The embroidery on the Colours was also silver, matching the helmet fittings and the colour of the buttons. Shortly after it was formed, the regiment was presented with the inspection march “Alte Marsch T” and the “Marschvom Regt. Prinz Heinrich” (March of the Prince Heinrich Regiment) which had been based at the garrison in Spandau under Frederick the Great. On 2 December 1914 the Chief of the Austrian General Staff, General Conrad von Hötzendorf, was appointed Regimentschef (Colonel-in-Chief of the regiment).

Uniform of the Regiment

Blue tunic; red collar with a broad white Old Prussian Litze(braid); Brandenburg cuffs with dark blue cuff patches (Ärmelpatten), and on these three white Old Prussian Litzen; white shoulder boards; white buttons; white leather equipment; leather helmet with white fittings and white helmet sockets (Helmbuchsen)1. Variations for non-commissioned officers: Tressen (silver lace) on the collar and cuffs. Variations for officers: Old Prussian silver embroidery on collar and cuff patches.

Uniform Changes:

15. 6. 1898: Cloth insignia on the right upper arm, gorget and special sidearm2 for standard bearers.

1. 5. 1899: Guards Litzen on greatcoat collar patches for NCOs and other ranks.

14. 3. 1902: Bandolier of red Juchten (Russia) leather with Tressen and “cup” for standard bearers.

27. 1. 1903: Semaphore insignia for trained semaphore signalmen.

16. 4. 1903: Grey Litewken for officers, NCOs and other ranks.

20. 12 1903: Shoulder boards to be worn by officers also on overcoats.

15. 6. 1905: Steel bayonet scabbards to be blackened.

13. 2. 1913: Medical NCOs and other ranks receive the uniform of the regiment with special insignia on the right upper arm and black Helmbuchse instead of the special uniform worn previously.

Additional Uniform Changes in 1913

The field grey uniform, introduced in 1907, is worn for the first time during the autumn exercises. Fieldgrey tunic with a flap collar and collar tabs (Patten); collar patches with a white Litze,and cuff patches with three white Litzen; matte buttons with royal crown; grey shoulder boards with white edging; a grey cotton scarf instead of the neck stock; fieldgrey caps with red trim; black leather equipment. Variations for officers: Litzen on collar and cuff patches are made of matte grey fabric, similar to the Litzen worn by other ranks.

------------

Note on 1907 Litzen:

There were two types of Litzen introduced for 5. Garde-Regiment for the rank and file and NCOs.

NCO old Prussian Style Litzen with measured 1.2 cm wide and 14cm long.

Standard old Prussian Style Litzen is 2.4 cm wide and 16 cm long. However, during the war, the 16cm long Litzen was shortened (by 1915) to 7 cm in length.

------------

In 1913, in the last army expansion, the 5th Guard Regiment was assigned a fusilier battalion (it had previously been without one), and in October 1911 a machinegun company* (every infantry regiment was assigned one machinegun company in the year before the outbreak of the war). From the beginning, it was the regiment’s proudest boast that in terms of its bearing and accomplishments this youngest Guard regiment was considered the equal of the old Prussian elite regiments. The regiment had already been noticed in its first year, when the 6th Company, under its captain, Hauptmann Freiherr von Horst, was awarded the Kaiserabzeichen (Kaiser’s Award), introduced on 27 January 1895, for the company with the best marksmanship in the entire Guard Corps. The officers and men soon became justly popular with the residents of the twin cities of Berlin and Spandau, who were wildly enthusiastic about all things military. Once the new regiment had taken part in several memorable Kaiser’s parades at Tempelhof and in exercises and maneuvers with the Guard Corps, the people of Berlin and the Mark Brandenburg, young and old alike, all knew the silver insignia of the “Spandauer”, who by then had become an integral part of the Prussian Guard Infantry. Being based near the military training area at Döberitz gave them a particular advantage in terms of soldiering and training.

The men of the “Fifth” were also envied because they possessed the military swimming baths, which they had taken over from the “Augustaner” (Queen Augusta’s Regiment), an unequalled source of refreshment for the whole regiment during the hot summer. The yacht “Niagara”, commissioned by His Majesty, was a very special honour and joy for the officers and a considerable addition to the many advantages of the Spandau garrison and the charms of the Havel landscape, compared to the stone desert of Berlin.

On 12 August 1914, following a farewell parade and review by General major von Below, commanding the 5th Guard Infantry Brigade, at which Lord Mayor and Privy Councillor Dr Koeltze conveyed the warmest blessings of the people of Spandau, and after a silent Holy Communion in the garrison’s churches, the youngest Prussian Guard regiment left for the field, with the sacred vow to fight faithfully for the honour of the Prussian Guard tradition embodied by the Colours presented to it by the Commander-in-Chief.

Early-War

(1914-1915)

The First Pour le Mérite

On 17 August 1914, units of the 3rd Guard Infantry Division1 of the Guard Reserve Corps under General der Artillerie von Gallwitz crossed the Belgian border between Malmedy and Stavelot. At the customs post on a bare hilltop, the regimental band deployed from line into column, and to the strains of the Preußen marsch and with a “Hurrah!” that seemed to last forever, the regiment marched proudly past its regimental commander, Oberst von Hülsen, and into enemy territory.

As his men marched past, the Oberst tried to read in the eyes and soul of each grenadier whether he was truly prepared to give his life for Kaiser, King and Fatherland. As he did so, he sensed such a calm, natural determination in every man that he was deeply moved and said a short prayer to Heaven: “My Lord, my God, help me to do right as I lead this magnificent regiment, this wonderful German youth, into the battles that lie ahead of us.”

Several days later, the battle of Namur began, where the regiment would receive its baptism of fire. With the splendid offensive spirit of the Prussian Guard, they expected to be able to break through the line of fortifications at Namur without artillery support, as at Liège several days before, and take this important Belgian fortified position by storm. On 22 August the regiment received its baptism of fire and passed with flying colours, the Fusilier Battalion at the Château de Beauloy, and the two Grenadier Battalions and the Machine Gun Company at Montigny and Wartet.

It was here that one of the youngest officers in the regiment, Leutnant von der Linde (Otto) of the 8th Company, performed an outstanding military exploit. He had been ordered by his battalion commander, Major Reinhard2, to take several men and reconnoitre towards Fort Malonne. He and his men went forward, climbing over several obstacles on their way, but no enemy troops showed themselves. Expecting to come under fire at any moment, they made their way as far as the main trenches. Finally they heard voices, and without hesitating, the Leutnant shouted over to the loopholes across from them: “Surrender at once! Resistance is useless! The artillery is in position, ready to fire on you!” They began to negotiate terms. The Prussian Guard Leutnant’s daring action had made such an impression on the Belgians that the commandant actually agreed to surrender the fort without a fight. Leutnant von der Linde himself took down the enemy flag. They quickly stitched together a black, white, and red flag from a pair of black Belgian trousers, a shirt, and a red sash, and raised it to show our troops that Fort Malonne was now in German hands. Based on the recommendation of his superior officers, the Leutnant was subsequently awarded the Pour le mérite by the Kaiser, the first awarded to a junior officer in the Great War.

Into the East

On 26 August the regimental commander, Oberst von Hülsen, had gathered the officers together in the church at Sart-Saint-Laurent and invited the commander of the Fusilier Battalion, Oberstleutnant Graf von der Schulenburg, to speak about his experiences in the attack, when an Ordonnanzoffizier (special missions staff officer) of the 3rd Guard Infantry Division brought the order to return to Aachen immediately. “That order”, relates the former regimental commander in the “Ehrenbuch der Preußischen Garde” (Prussian Guard Book of Honour), “had such a demoralising effect. It destroyed our hope of going up against the French in open battle”.

In Aachen, where the regiment was greeted with cheers, Oberst von Hülsen received the news that he had been appointed Chief of the General Staff of the Marine Division. With a heavy heart, he said goodbye to the unit which, under his command, had added the first laurel branch (battle honour) to its new Colours. Appointed as his successor was Oberstleutnant von Radowitz, the former commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Guard Grenadier Regiment, which was part of the same brigade.

They travelled across Germany to the East. Here, the 8th Army had had to fall back from a numerically superior enemy, but the Kaiser had given it a new commander, General von Hindenburg, who had been living in retirement in Hanover. Generalmajor Ludendorff, who had made a name for himself by capturing Liège, joined him as his Chief of Staff.

They had already fought and won the battle of Tannenberg while the 5th Guard Regiment was still on its way back to Aachen. But once the regiment had arrived on East Prussian soil at the beginning of September, the Guard Reserve Corps went on to fight at the Battle of the Masurian Lakes, where Hindenburg had a bloody fight with General von Rennenkampf’s Russian Niemen Army from 6–12 September 1914.The battle, as is well known, marked the final liberation of East Prussia from the Russian invasion.

The regiment was not involved in any significant fighting in the Battle of the Masurian Lakes, but it was required to march unprecedented distances on poor roads and in bad weather. In just under 14 days, the regiment had completed a march of 260 kilometres, good preparation for the hardships that awaited them in the two forthcoming Polish campaigns.

“We are the Travelling Guard Reserve Corps; all aboard for the railway tour!”, sang the men. Indeed, on 17 September they were back on the train again, but it did not take them back to the West. When they had a look around the next evening, they discovered that they were in the south-eastern corner of the monarchy, in Upper Silesia. The people of Tarnow ice breathed a sigh of relief at the arrival of the Prussian Guard, as they had expected a Russian invasion and had been preparing to flee.

Several corps had been detached from the old 8th Army to form a new 9th Army under the command of Hindenburg. Together with the Austrians, it was ordered to mount an offensive from Upper Silesia and the Krakow region against Warsaw. The regiment fought heavy battles during this first Polish campaign, particularly at Nowo-Aleksandrija from 9–11 October and the battle of Ivangorod from 12–15 October. There was hard positional fighting outside this fortress until the 20th. The regiment was subjected to heavy Russian artillery fire, but the Spandau grenadiers fought off the Russian attacks with well-aimed rifle and machine gun fire at close range.

But the German army was too weak to achieve its objective, the capture of Warsaw. It had to be withdrawn, and over the next few days it fought a series of battles with the advancing Russians. Both sides fought with the utmost ferocity. There was a particularly bloody battle on October 24, in a wood at Sewery now. The two Grenadier Battalions took the Russian position in a surprise attack. To their left, the 11th Company under Hauptmann Herwarth von Bittenfeld was advancing towards a clearing, when it suddenly came under surprisingly strong Russian rifle and machinegun fire. As he went forward, Fähnrich von Lützow, the battalion commander’s son, was wounded, shot in the thigh. When he reached the front line, he got up to see if the men of his platoon had all followed him. His Hauptmann shouted a warning: “Fähnrich, get down!” As he did so, he was hit in the neck and jaw, and fell, mortally wounded. With the last of his strength, he threw his binoculars to his range estimator. Seeing his Hauptmann fall, the Fähnrich, despite being wounded himself, attempted to go to his aid, but was hit a second time, in the chest. He fell, severely wounded. The men of the 11th Company were under heavy fire and taking casualties. A wounded man brought bad news to the battalion commander, Hauptmannder Reserve Freiherr von Lützow: “All the company officers are dead, and the Fähnrich is badly wounded.” The battalion commander immediately sent in the 10th Company, which he had been holding in reserve. It carried the 11th Company forward with it in the assault. Its men had a burning desire to avenge their much-loved Hauptmann and the promising young Fähnrich. But the Russians did not stand. The two companies were still 100 metres from the edge of the wood, when the Russians threw down their rifles and ran towards the fusiliers with their hands raised. The Fusilier Battalion took 700 prisoners.

Meanwhile, its commander, the father of the severely wounded Fähnrich, had been going through a difficult time. As he himself relates: “Collecting the prisoners for transport to the rear, evacuating the wounded, leading the battalion to a new rallying position as the Russians were preparing a counterattack, all took a superhuman degree of self-control, for a few paces away from me my son lay dying. There was no question of transporting him to the rear. The thought of having to leave him lying there filled me with despair. Then, finally, Unterartzt (assistant surgeon, a warrant officer) Dr Rettschlag came and told me that it was nearly over. I had to look on that as a release, for my son was suffering terribly. We had no morphine, since the Russians had captured our ambulance wagon on the 21st. My son recognized me and asked me to remember him to his mother and his brothers and sisters. Then he said to me: “There’s something really big coming!”–and with that, his suffering was over.

We could not bury our dead. We had to leave them. Only Hauptmann Herwarth von Bittenfeld and my son were not left lying thereby the good fusiliers. They carried them on their capes far enough back for us to be able to give them a rather hurried burial, expecting the Russians to appear at any moment. I dug my son's grave with my own hands near a wood cabin under the tallest fir tree and used the axe to mark his grave on the tree.”

During that time, Generalleutnant Litzmann, whose name is forever associated with the fame of the 3rd Guard Infantry Division, took command of the division. He himself describes this most significant event in his life: “On 18 October 1914, I was at my Main Depot in Rethel (Generalleutnant Litzmann was initially the Line of Communications Inspector of the 3rd Army in the West), standing in front of the shaving mirror, my chin covered in shaving soap, when my adjutant at the Inspectorate, Oberleutnant Globig, rushed into the room in a state of excitement. “What is it?” “Your Excellency has been transferred to the East, as commander of the 3rd Guard Infantry Division!” The first thing I did was to cut myself good and proper with my razor, which I had just applied to my chin; the second was to tell the likeable Saxon Guard cavalry officer, somewhat brusquely, that “I will not have jokes like that!” I, a man in my 65th year, unknown, and with a rather unstatesman like appearance–commander of a Guard division on active service? That went against all tradition and seemed impossible to me.

And yet, it was so. On the anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig, my greatest fortune thus far as a soldier had fallen right into my lap. And on the 22nd, the birthday of our most revered, never-to-be-forgotten Empress, and of my wife, similarly immortalised in the meantime, I took command of our beloved division. That was at Glowaczow, on the Radomka.

Old Jäger and soldiers tend to be superstitious; I was convinced that it was a good omen for me that such dear and eminent memorial days should coincide with these important milestones in my career as a soldier. And I was not mistaken! I soon felt at home on the superb Divisional Staff, and as for our troops –there have never been any better soldiers, anywhere in the world!

Two men that are brothers in sister Regiments. The man on the left is from G.G.R.5. and appears to be a Unteroffizier. The man on the right is of 5.G.R. Picture was certainly taken in the east.

Over the next few days –during the fighting at Brzuza and in the woodland area west of Ivangorod – I would discover their excellent training and battle discipline, their outstanding proficiency, and their absolute dependability. Their wonderful spirit of discipline and faithful dedication also shone forth during the subsequent withdrawal to Upper Silesia. It was our Austrian allies, not us, who were responsible for the retreat. Our people knew that they had done their duty and always would! They marched in perfect order, with their heads held high and cheerful defiance in their hearts. Not once did their soldiers’ songs fall silent on any day of that withdrawal.”

The advance of the 9th Army into Warsaw had failed, and it had to withdraw in the general direction of Upper Silesia. Our eastern provinces of Posen and Silesia were under serious threat, for even a temporary occupation of the industrial region of Upper Silesia by the Russian armies would have had incalculable consequences for our armaments industry, and thus also for the military situation on the Western Front. So this time, Hindenburg ordered an attack on the flank of the four Russian armies facing the Germans, as it was impossible to oppose them head-on. This meant that large parts of his army had to be transported by rail – among them, naturally, the “travelling” Guard Reserve Corps– to the Hohensalza-Thorn region, to strike against the right flank of the advancing Russians. The unexpected thrust took the Russians completely by surprise, and their 2nd Army was pushed back to Lodz.

It seemed that there might be a second Sedan, or a second Tannenberg. While Hindenburg had been appointed Supreme Commander East and, together with his Chief of Staff Ludendorff, was in overall command of the operations from Posen, the main bulk of the 9th Army, now under the command of General von Mackensen, formerly commanding the XVII Army Corps, was now closing in on Lodz, the “Manchester of the East”, in the south and north. General von Scheffer-Boyadel’s Armee-Abteilung*, however, to which our 3rd Guard Infantry Division belonged, was ordered to proceed via Brzeziny-Bendkow in the direction of Rzgow-Tuszyn and then attack further west from there to link up with the Frommel Cavalry Corps near Pabianice. Then the Russians would be stopped; if all went well, Scheffer’s march against the enemy's rear would result in the surrender of the 2nd Russian Army at Lodz.

The Spandau grenadiers went via Kreuzburg–Ostrowo – Hohensalza to Argenau (near Thorn) where the regiment disembarked. They marched south, making forced marches off at least 40 or 50 kilometres per day, marching from sunup to sundown in cold, wet weather and icy wind, mostly on unsurfaced roads and with poor quarters. Everywhere they came across signs of the recent battles; the road along which they advanced was lined with dead Russians, many Cossacks among them, dead horses and discarded equipment; the towns they passed through were either badly shot up or completely burned to the ground.

“The White Devils”

On 18 November, the 5th Guard Regiment took part in its first fight in the Battle of Lodz, which began on that day and ended on 6 December with the occupation of the city. It had the opportunity, as loyal brothers in arms, of assisting the young Kriegsfreiwillige (volunteers) of the XXV Reserve Corps at Niesulkow; the enemy was put to flight and fell back to Grzmionka, and the road to Brzeziny was open. Six Siberians in tall fur caps were brought in, attracting much attention. Then the regiment arrived at Brzeziny, where the companies were assigned their quarters. Meanwhile, however, the 1st Russian Corps was advancing from the south towards the village and country estate of Malczew, which had been assigned to the Regimental Staff and the 1st and Fusilier Battalions. The Regimental Staff rode ahead of the battalions from Brzeziny to Malczew. No sooner had they arrived at the grange – as Ordonnanzoffizier Leutnant Freiherr von Maltzahn relates – when suddenly a cry rang out from close by: “Stoi! Kto tam! Propusk!” A devilish predicament, all the more so when they suddenly came under heavy fire from close range.

“We turned and galloped back the way we had come. It turned into a real race, as the horses were very agitated by the shooting. We galloped through the darkness. My Lotte took the lead. We came to the point where we had turned off into the estate and where we now had to make a sharp right turn. That would be our undoing! I ran into a crucifix, and my trousers were hanging off me in tatters. At that moment, I saw two riderless horses gallop past me. That gave me a real shock since I had to assume that Oberstleutnant von Radowitz and Oberleutnant von Teschen – the regimental commander and his adjutant – had been hit and had fallen from their saddles. Fortunately, Teschen turned up again. He too had fallen from his horse at the crucifix. But he had not seen the regimental commander since. A patrol was sent out to look for him.” It should be noted here that during the fighting that followed, the 1st Battalion in Malczew received the message that Oberstleutnant von Radowitz was in Brzeziny. His horse had been shot from under him at the infamous bend in the road. When he got to his feet, the regimental commander found that he had bruised several ribs. Despite this injury, he had managed to drag himself 4 kilometres across freshly ploughed fields back to Brzeziny and had escaped capture by the Russians. Orders came for the Fusilier Battalion to occupy the Malczew estate and for the 1st Battalion to advance towards the village. With fixed bayonets, the Fusilier Battalion headed for the estate. The 1st Company was advancing in open order towards Malczew village, when suddenly it came under heavy fire from 40 metres away. The brave commander of the 1st Company, Hauptmann von Seeler, fell, shot through the heart. At around 11 o'clock, the Regimental Staff were informed that the situation up front with the 1st Company was not looking good. The other companies were committed, and they remained in the standby positions the whole night, in the icy wind.

Meanwhile, the Fusilier Battalion under Freiherr von Lützow, who had been promoted to Major, had reached the Malczew estate. Finding it to be free of enemy troops, they prepared the grange for defense. The companies found warm quarters in the stables. Just as it began snowing heavily, the Russians began to attack. The Fusilier Battalion of the 5th Guard Regiment was about to fight one of its toughest battles of the entire war. The Russians advanced in close order from three sides at once, but the companies had been able to take up their positions in time. The eastern side of the estate was held by the 9th Company under Leutnant der Reserve Schreiber, and the southern side by Hauptmann von Reibnitz with his 12th Company. The 10th Company under Oberleutnant der Reserve Paulentz was in position north of the estate, and the 11th Company occupied defensive positions behind a barn on the western side. In view of his battalion’s critical situation, which could potentially influence the overall situation of the division, Major Freiherr von Lützow had immediately made contact with the regimental commander in person at Malczew village. But he could not get back to his fusiliers, since in the meantime the Russians had the estate surrounded on all four sides. This left his adjutant, Leutnant Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach (Heinrich) in temporary command of the battalion. A fellow combatant, Leutnant der Reserve Haendler, relates: “The air rang with the sharp cracks of the Russian bullets. We were taking casualties, and we could hear the cries of wounded men in the positions. The troops lived up to the highest possible expectation: with iron discipline, they offered no resistance under the heaviest enemy fire! The order was given to hold their fire, which they obeyed to the letter. Not a single shot was fired until the enemy got in close. Only then was the order given to open fire. The Russian attacks became ever more ferocious and bitter. With fierce determination, the enemy drove his ranks forward again and again into the grange. All through the long night until dawn, the Russian attacks came at short intervals, never letting up. Several times, the Russian ranks got close to the edge of the estate, and at times a few Russians even managed to get inside. The wounded were gathered together in a single room of the grange.” There, Feld-Unterarzt Dr Rettschlag worked tirelessly and selflessly at his trade. The wounded, who were only able to follow the fortunes of the battle from the noises that filtered through to them, suddenly got an idea of the situation when they heard Dr Rettschlag shout: “Damn it! Rifles!” A few lightly wounded men were already rushing to the door, rifles at the ready. Some Russians standing in the doorway were put out of action at the last moment. “And so the fighting raged on,” Leutnant Haendler continues, “hour after hour! Our initial fatigue, our hope of getting a refreshing night’s sleep, were long since gone, any thoughts of rest forgotten, nerves strained to the limit. All four companies stubbornly withstood attack after attack with equal bravery and defiance in the face of death. Their courage was exemplary.” Another fellow combatant, former Kriegsfreiwilliger Strube of the 11th Company, recalls, “In the twilight, we could see the Russians rushing forward in close order. We could hear their attack signals and commands clearly. The enemy was about 250 metres away. Tense and anxious, our fingers on our triggers, we waited for the order to open fire. No-one said a word, not even the young Ersatz reservists.* We demonstrated superb self-control and marksmanship training. The Russians came closer and closer – 200, 180, 150 metres – then a shrill whistle blast cut through the winter’s night, and we unleashed death and destruction on the Russians. The massed ranks stopped short, then turned and fled. Only a few, undaunted, ran on through the killing ground and reached the edge of the grange. We took them out at a few paces. Those who were not killed were taken prisoner. The remnants of the Russian battalions retreated, with well-aimed fire still taking its toll on their ranks.” Leutnant Haendler takes up the story once again: “While recognising the exemplary courage of every individual, particular mention must be made of the actions of the brave and universally popular young Leutnant Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach in those terribly difficult night hours. The situation of the Fusilier Battalion was desperate. It could perhaps have made a hasty withdrawal to Brzeziny, but that would have put the division in a most dangerous position. Making a stand at the grange could either bring victory or end in the destruction of the battalion.

Mindful of the heavy responsibility he bore, the battalion adjutant kept a cool head and took the courageous decision to “hold the grange, at all costs”. His uncompromising resolve then naturally became the common objective of the whole Fusilier Battalion. With iron determination and vigour, Leutnant Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach gave clear and motivational orders and carried out his decision, giving them a chance of victory. The success of the action proved him right. By his dogged determination alone, he was able to harness the unmatched tenacity and resilience of the troops in the face of vastly superior enemy numbers and gave them a chance of victory. Only in this way were they able to hold the Malczew estate throughout the night.”

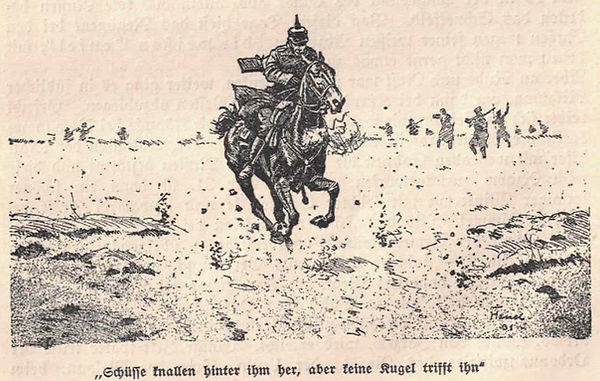

There was still the danger that the beleaguered battalion might run out of ammunition and that, despite all its courage and valour, it might be overrun by the next Russian assault. At first light, once the fighting had calmed down somewhat, the Leutnant set off on his horse to make contact with the regiment. Thick early morning fog lay on the ground, it was still snowing, and visibility was limited. Suddenly his horse shied away. He had run into the Russian lines, where the enemy troops had dug in facing the estate. But fortune favours the bold! The brave horseman galloped straight at the human obstacle and cleared it in a high jump. Shots rang out behind him, but none of them hit him, and he reached the 1st Battalion safe and sound.

At 8 o'clock in the morning, the Russians attacked once again. As they had not succeeded during the night, they were probably hoping that the battalion, tired and exhausted from battle, would no longer put up much of a fight. But the fusiliers were at their posts. Their battalion commander, Major Freiherr von Lützow, had arrived back at the estate from Malczew village via a dangerous road that was constantly under fire, and had taken over command of the battle. The Russian ranks advanced relentlessly, when suddenly the first German shells – from the 3rd/6th Guard Field Artillery Regiment – burst among them, greeted with cheers from the fusiliers. A machine gun company from the Leer Infanterie Regiment under Hauptmann von Reiche, which had been brought up by Leutnant Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach personally, also joined in the battle, and the Russian attack finally broke. Many Russian troops threw away their weapons and surrendered. Four officers and 258 other ranks were taken prisoner. The young Ersatz reservists were proud to have come through their baptism of fire so splendidly. But the area around the estate looked grim, with 800 Russians alone lying dead in the snow-covered field. From that day on, the Russians knew the regiment (from their white insignia) as “die weißen Teufel” (“the White Devils”), a unit that they would not want to face in battle.

But there was no time to rest or to take it easy. They continued south and then turned sharply west at Karpin. They fought battle after battle. Only a brief mention is made here of the battles at Romanow-Kalinko, where, alongside the 3rd Battalion of the “Maikäfer”1, they stormed the Russian position with their Colours flying, and threw the Russians back to Rzgow. On the 21st, a beautiful, sunny winter’s day with a light covering of snow and a slight frost against a blue sky, the Fusilier Battalion marched past General von Scheffer, the commander of the Armeeabteilung – an old “Alexandriner”2, himself – who commended them on their good order and told their commander that he had seen the regiment go in at Kalinko the day before: “Wonderful, just like at Döberitz.” Then Major Reinhard turned northwards, towards the southwestern suburbs of Lodz. They reached Dombrowo, south of Zarzew. Sometime later, the regiment’s Ordonnanzoffizier, Leutnant Freiherr von Maltzan, reported to the regimental commander that he had met General Litzmann on a hill near Wiskitno. His Excellency could hardly believe that the 5th Guard Regiment had already reached Dombrowo and had said these exact words to him: “The 5th Guard Grenadier Regiment is engaged in heavy fighting at Olechow. My compliments to your illustrious commander on reaching Dombrowo. I expect him to hold there at all costs, until the Grenadier Regiment can get clear. The 6th Guard Infantry Brigade (Lehr-Infanterie-Regiment and Guard Fusiliers) appears to advancing and will be coming up from the east.”

Lodz being only one or two kilometres away, it was understandable that the men should be tempted to make a little detour. Unteroffizier Elfeldt and two men set off on their bicycles, hoping to take a couple of Cossack prisoners, as they had heard so much about them. Some German-speaking inhabitants approached them and asked them when the Germans would be occupying the city. They shook the hands of the men from Spandau, very glad to greet their fellow countrymen. The men made some purchases at the baker’s and the grocer’s, while one of their group kept watch outside. Then, suddenly, the Russians arrived. First there was some frantic shooting, and then the chase began. In the end, some Cossacks also joined the chase, reluctant to let the enterprising patrol get away unscathed. Naturally, when they arrived back at the company, the three men got a good dressing down for their foolhardiness. Afterwards, one of the cyclists, Gefreiter Wozny, discovered to his surprise that his left hand was covered in blood and his little finger was missing. It had been shot off. But he felt no pain. He looked in astonishment at his bloody hand and then at his split handlebars, part of which had evidently also been hit, and found the missing little finger inside the tube.

So the hours passed, until 2.30, when a Russian aircraft suddenly appeared. Immediately afterwards, the many church bells of Lodz all rang out for 10 minutes like a distress call. It sounded truly solemn. In the evening, a red column of fire flared up over the city, and moments later, three equally bright beams of light were observed to the south, north and north-east. Russian reinforcements, heralding the approach of the hard-pressed Russian 2nd Army! The regiment was in a critical situation, all alone in the pitch darkness, with only itself to depend on. As General Litzmann later related in his memoirs: “Nobody in the entire area got this close to the city. Reinhard showed what audacity could do!”

“Brzeziny Spirit”

That same afternoon and evening there had been a skirmish in Brzeziny, which lay on the road used by Armeeabteilung Scheffer for its withdrawal. Cossacks and Siberians of the 6th Division had pushed their way into the town and drunk all the alcohol supplies at the field hospital there. They were in very high spirits, as one can easily imagine, given the strictly enforced liquor ban in the Russian Army. Leutnant von Witzmann (Helmuth) of the 5th Guard Regiment had been shot in the neck in the fight at Kalinko. They had just dug the bullet out when the Russians burst into the town. He quickly assembled all the men of the perimeter guard, who had fallen back to the market square, and some lightly wounded men from all units. The Siberians came stumbling down the road, yelling loudly. Leutnant von Witzmann had deployed his men across the width of the road. It was pitch dark. Once the drunken mob got to within 15 paces, they were met with three volleys followed by rapid fire. The Siberians broke and fell back en masse, encouraged in their flight by Leutnant von Witzmann and his men, bayonets fixed, in hot pursuit. He threw them right out of the town. The staff at the field hospital and the patients, who had had to form up ready to be transported into captivity, were set free. The Spandau Guard Leutnant’s fearless exploit, which earned him the Iron Cross, 1st Class – the first in the regiment’s 2nd Battalion – was the talk of the Eastern Front for quite some time afterwards.

Totensonntag (literally “the Sunday of the Dead”)* dawned dull and grey. This was to be a particularly difficult day for the regiment. “Attack on Olechow.” That was the order Major Reinhard received from brigade. The 3rd Battalion of the Guard Fusilier Regiment was already engaged against the eastern flank of that village, actively supported by the 1st and Fusilier Battalions of the 5th Guard Grenadiers. The regiment was assigned the south-eastern flank of the village as its attack sector. As Reinhard's battalions advanced, they were met by shell and shrapnel fire from the north, west and southwest. With his arm in a sling (his wound from Namur had not yet fully healed), Hauptmann von Reibnitz, who had taken command of the 2nd Battalion, was following the dispersed companies on horseback together with his adjutant, Leutnant von der Linde. The latter, whom we already know from his capture of Fort Malonne, relates: “Out in front of the 7th Company, their brave commander, Leutnant der Reserve Dangers, was charging forward ahead of his loyal grenadiers. As he ran, the young officer was killed, shot in the stomach. The 7th was without a commander. The company was beginning to falter. Nothing escaped the sharp eyes of the battalion commander.

He shouted to the adjutant: ‘The 7th has no commander. We have no more business here. I’m going to lead the battalion from the head of the 7th Company. Come on!’ With that, he put his spurs to his horse and rode after the 7th, right into the heart of the devastating fire. They reached the rear ranks of the 7thwhere they dismounted, and the battalion commander strode to the front of the company. ‘Bugler, play “Fix bayonets”!’ he shouted and charged forward, taking the whole company along with him. The Russian fire was now twice as heavy. Bullets were ricocheting all around us off the frozen ground. But there was no stopping the 2nd Battalion now! They ran on, crossing the stream bed without breaking their stride. They had reached Olechow! The Russians put up a desperate defence. Hauptmann von Reibnitz ordered the bugler to blow ‘Attack’, and with a mighty ‘Hurrah!’, their brave battalion commander in the lead, the grenadiers charged at the village.” His adjutant, the young hero of Namur, fell on the village road, badly wounded in the chest and shoulder, and a moment later the heroic Hauptmann von Reibnitz was also fatally wounded on the other side of the village. But the battalion charged on over their fallen commander and won the victory. Inspecting the captured machine guns, the grenadiers shook their heads in disbelief at the company stamp “Ludwig Löwe u. Co., Berlin”. That was all they needed after taking such horrendous losses! On the other hand, the help of the Lancelle battery from the 6th Guard Field Artillery Regiment was gratefully acknowledged. In a farmhouse in Wiskitno, where they had taken him, the heroic Hauptmann von Reibnitz took his last breath: “I’m in a bad way. But we have Olechow, and that’s the main thing. The victory is ours.” Those were his last words.

Late that evening Major Reinhard received the order to report to the divisional commander, General Litzmann, in Wiskitno. On the way, he ran into a figure with a heavily bandaged head. It was Leutnant von Witzmann, whom we know. He reported that Brzeziny had had to be evacuated. Siberian troops had attacked in force. The few guards and lightly wounded men were outnumbered and could not have held out. He had been wounded again in the withdrawal, his head grazed by a bullet. He and his men had fallen back to the south, in order to re-join the regiment. He once again took over his duties as adjutant with the 2nd Battalion, in place of the wounded Leutnant von der Linde.

Leutnant von Witzmann’s report had shown Major Reinhard how serious things were. If the Russians were in Brzeziny, then Armeeabteilung Scheffer was surrounded on all four sides, just like the Fusilier Battalion at Malczew a few days before. There were only two alternatives: to surrender ignominiously, or to carve their way through the enemy ranks – or die trying.

In Wiskitno, His Excellency General Litzmann explained the gravity of the situation to the commander of the 5th Guard Regiment. He continued: “You and your proud regiment have performed considerable services for me on many occasions. Twice you appeared with your troops exactly where the tactical situation required you to be, even without direct orders, and you have made a decisive contribution to many of the division’s battles. The service I must now ask you to perform is the most difficult one of all, and perhaps the last. You will first form the spearhead, then the flank guard, and finally the rear guard for the division’s withdrawal. You will form up as the spearhead immediately.” He then gave further details of the composition of the detachment under Major Reinhard’s command. The two officers parted with a handshake.

“The blood-red sunset on Totensonntag, which had lived up to its name with the deaths of many fine German soldiers on the blood-soaked killing field at Lodz, gave way to an ever-worsening frost”, relates Major Reinhard. “A biting wind blew across the bleak, barren mountain range, chasing the last snow clouds from the sky. As the field guns gradually fell silent, the calm broken only by sporadic rifle fire, night fell over the battlefield, the stars visible against the clear night sky above the winter landscape. There was no moonlight. After 36 hours of gruelling fighting, everyone was half-starved and shivering with cold. Still no prospect of warm quarters, or food, or rest. The coffee in the canteens had frozen, and men who still had a piece of bread were thawing it out laboriously in their mouths. But if the valiant Germans were tired, the Russians were even more so. They were sleeping, despite the first stirrings in the German lines. Meanwhile, Reinhard’s composite detachment trudged along in the relentless monotony of the barren Polish countryside, marching slowly through the endless icy night. It would not be the last.”

During the night the remaining troops of the 3rd Guard Division withdrew, leaving no wounded behind for the enemy. They now headed north again, towards Brzeziny, all the while in contact with the enemy. Meanwhile, the division received an attack order from General von Scheffer. Litzmann and his troops were to attack through the wood to the west of Borowo. Given the extremely tense situation, the commander of the 3rd Guard Division took the momentous decision to break through to Brzeziny, regardless of developments in the battle with the XXV Reserve Corps.

Reinhard and his detachment, with the Fusilier Battalion in the rear guard, had covered the division's withdrawal, but now he received the order to re-join it. Upon arrival, he was ordered to advance through the wood to the west of Gora-Zielona, take the enemy-occupied railway embankment and keep moving through the wood. The short winter’s day was coming to an end, and Reinhard deployed his battalions at dusk. They advanced, with the 2nd and 1st Battalions in front and the Fusilier Battalion in the centre. The railway embankment was unoccupied. A little later they heard an exuberant “Hurrah!” from the east, where the Guard Grenadiers and the 6th Guard Infantry Brigade were storming the railway embankment. At the head of the Pioneer Company of the Division’s Küstriner Battalion was the divisional commander, with drawn sword. He himself gave a gripping account of this event in his memoirs.

But the division had to keep moving, Brzeziny had to be taken, or the other elements of Armeeabteilung Scheffer were done for.

In a farmhouse at Galkowek-West, which had been captured from the enemy, the commander of the 5th Guard Regiment waited for the divisional commander. Reinhard asked the General to allow the troops, who had been fighting for days now, to rest for a few more hours. But General Litzmann shook his head. He told the Major how desperate the situation was with the neighbouring division, and then concluded: “I must save the infantry for the King. Your regiment is the spearhead, Reinhard. Talk to your men. Tell them to keep going.” A few minutes later, the regiment was formed up on the village road. “Men, can you still carry on?” asked the regimental commander, and the brave men, who had been in battle continuously for three days, answered with a confident, if tired, “Jawohl, Herr Major!”

The division moved out at 10 in the evening, advancing in severe cold across frozen ploughed fields towards enemy-held Brzeziny. General Litzmann dismounted, and leaning on his shooting stick, followed by his Staff, he joined in the arduous march at the head of the regiment.

At midnight they reached Galkowek, to the north of the wood. They formed up without a sound. The men unloaded their rifles and carried their rifle bolts in their trouser pockets, so that no shot would give away their approach. The sleeping Siberians were roughly woken and roused from their straw, and as Major von Bonin had the prisoners form up outside, General Litzmann, delighted, said to him: “I did not believe that the day would turn out so well. I thought that pockets of infantry would make it through at best, and the rest would be lost.”

The march went on. Just when they were beginning to wonder if they had lost their way, they came upon the grave of Hauptmann von Seeler, who had been killed on the 19th at Malczew. That was an unmistakable signpost. At 3 in the morning they reached Brzeziny. As they had done at Galkowek, they formed up, unloaded their rifles and put the bolts in their pockets. A Russian perimeter guard, caught napping, was dealt with silently, and Litzmann's grenadiers moved into the sleeping town without firing a shot. They went in silently with rifle butts and bayonets, and any enemy who did not surrender was cut down. But our side also suffered losses. The brave Oberleutnant der Reserve Hinze was killed, shot through the forehead by a Cossack officer’s revolver.

But the troops were only able to rest for a short time. An hour later, the Russians attacked again. Major Reinhard, appointed local commander by the divisional commander, had the bugler sound the alarm. As the wind was favourable, the pioneers set fire to part of the town, smoking the invading Russians out again.

That same morning, Litzmann and his division moved into the high ground south of the town. All eyes were on the south, where shrapnel bursts appeared on the horizon. The XXV Reserve Corps, which had been struggling hard the day before, had been considerably relieved by the advance of the 3rd Guard Division, and was now driving the Russians back, right into the path of the Guards. As His Excellency General Litzmann relates in his memoirs: “My riflemen let out a huge cheer as they lay in the snow. All the hardship and toil of the last few days, all the hunger, cold, danger and fatigue, were forgotten. We were all filled with an almost wild joy. I myself snatched the black, white and red pennant of the Divisional Staff from the orderly, who was holding it under cover on the reverse slope, as prescribed by regulations, and pushed the tip of the steel lance into the ground at the crest of the hill. Now the Russians would see that they had a German division behind them!”

General von Scheffer and his Staff rode into Brzeziny at around 5 that afternoon. General Litzmann greeted him outside his divisional headquarters, the pharmacy on the market square. The commander of the Armeeabteilung took the hand of the heroic commander of the 3rd Guard Infantry Division and shook it firmly. “I congratulate you on yesterday’s victory,” he said. “That victory alone allowed my corps to be saved and enabled it to succeed. You have my thanks.” In his memoirs, General Litzmann recalls those days proudly: “A fervent love of the Fatherland, a strong sense of German honour, heroic self-sacrifice, iron discipline, the most loyal comradeship and the tenacious, steadfast will to win; these were the moral strengths that inspired the German soldiers of all ranks and forged the spirit which assures victory even under the most arduous circumstances: The ‘Brzeziny spirit’.”

Hand-to-hand

The decisive battles that followed in 1915, initially fought in the East, also entailed almost superhuman hardships and exertions for all of the units involved. The Spandau Gardisten took part in the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes, which went on for nine days, protecting the 10th Army’s left flank. Making relentless marches through deep snow, despite poor quarters and major supply problems, they protected General oberst von Eichhorn’s bold advance, enabling the second great German victory in the East. Here and in the ensuing battles in Northern Poland, the cry of horror - “The White Devils!” - would ring out time and again, in Russian or broken German, as soon as the enemy recognised the feared Guard infantry with the white insignia. In the fighting at Dunaj on 7 March, hundreds of enemy troops threw down their weapons with that fearful cry, making no attempt to put up a fight. Their officer, who was taken prisoner along with them, explained under questioning that his men, who had faced the regiment in battle before at Ivangorod and Lodz, were of the firm belief that only human devils could go forward under fire as these troops did! Soon this extraordinary honorary nickname would even come to be used in the German Army as well, as evidenced by the words of gratitude of the brigade commander, Graf von der Goltz, during the glorious pursuit actions in the lower Narew: “I was not mistaken about the White Devils. Gonzewo will forever be a great day in the history of the Fusilier Battalion and of the regiment.” At that time, the regiment was taking part in the great summer offensive in Poland, which, by order of the Supreme Commander, would draw the final stroke under the previous successes of the allied German and Austrian armies in Galicia, notably Mackensen’s breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow and the names Przemysl, Lemberg and Suwalki. On 22 July, the 2nd Battalion made its famous assault on the factory and village at Miluny, where the youngest Guard regiment of the Army would demonstrate its tremendous attacking power. From the regimental history:

“The assault had been prepared to the last detail. The 2nd Battalion was formed into two lines, with the 5th and 6th Companies under Leutnant von Sittman and Hauptmann von Teschen in the first line and the 7th and 8th Companies under Leutnant von der Linde (Otto) and Leutnant der Reserve Schütze in the second line. Each line was formed into three assault waves. Despite a heavy artillery bombardment on the Russian position, the enemy wire was still largely intact. The assault began at 1:28 pm. Although the Russian factory was still heavily occupied, the two leading assault companies broke through the wire with relatively few casualties. While the 5th Company was cutting the wire, Gefreiter Stroh, accompanied by Grenadiers Hense and Stefanik, rushed two Russian machine guns which had just gone into action and were firing on them. Despite being lightly wounded in the left arm, the determined Gefreiter Stroh ran on with his two comrades towards the machine guns. The gun crews – an officer and six men – put up a stubborn fight, but the three brave men managed to take them out and brought in three prisoners. Both machine guns fell into the hands of the 5th Company, which, together with the 6th and 8th Companies, pushed on into the factory. Once the factory had been cleared of enemy troops, the three companies entered the village of Miluny. Here the Russians offered fierce resistance, and tough hand-to-hand fighting ensued through the streets and houses. The attackers succeeded in clearing the village at bayonet point, reaching the exit road on the far side. As the 8th Company fought through the village in extended line, driving the enemy back through the orchards, its commander, Leutnant der Reserve Schütze, who was about fifty metres out in front of his men, went down, hit by a ricochet. His two loyal range estimators, who had been with him since war broke out, tried to crawl forward to where he lay so they could bandage him up. But they came under brisk rifle fire from Russians in a rallying trench and were prevented from reaching their wounded commander. So the grenadiers of the 8th Company started digging with their entrenching tools, and after an hour the centre platoon had worked their way up to the company commander and were able to get him into cover and dress his wound…

Miluny and the regiment’s positions came under heavy Russian artillery fire until late that evening. Rittmeister Graf von Geherr perceived that there was a serious threat to Miluny and the 2nd Battalion’s position from strong Russian positions to their right on the far bank of the river Roshanitsa. From his observations, however, those positions and a farmstead to their front appeared to have been cleared of enemy troops. He sent out Leutnant der Reserve Straßmann with his platoon from the 7th Company with orders to occupy the farmstead and the Russian factory and to cover the 2nd Battalion’s right flank. Straßmann’s platoon met only light resistance and achieved its objective, taking another 67 prisoners. In total, the 2nd Battalion had taken 552 unwounded prisoners, including two officers, and captured three machine guns and countless rifles and ammunition. Out of a total of 350 Russian dead, 250 lay in Miluny alone, and about 75 of those had died from bayonet wounds. Evidence of how tough the battle for the village had been!”

Rittmeister Graf von Geherr-Thoß closed his combat report with the words: “The grenadiers of the 5th and 6th Companies fought with admirable courage. Every one of them deserves to be awarded the Iron Cross!” The well-known author Ludwig Ganghofer was present at the battle, at the divisional commander’s side in the regimental command post. Moved by this heroic action, he wrote these immortal words: “The shining deeds of these two victorious hours shall be written in gold letters in the chronicle of the Prussian Guard!”

Prussians and Bavarians

While the 2nd and Fusilier Battalions were operating purely in an infantry role, the 1st Battalion under the command of Major von Bonin, attached to Generalleutnant von Hellingrath’s 1st Bavarian Cavalry Division, experienced a remarkable seven-month period of exciting operations which took a unique course. The North German Gardisten worked day to day in close comradeship with Bavarian cavalry, Jäger1, machine-gunners, cyclists, pioneers and horse artillery. Experiences such as this were unusual during the War, with its static front lines bogged down in a large-scale technological Materialschlacht2. This was a return to more dynamic mobile warfare, with its constant surprises, continually changing battle situations, and great demands on the intelligence of the leadership and the soldiering abilities of the troops!

The entry in the war diary for the battle at Kielmy, for example, reports: “The Bavarian cavalry division had attacked withdrawing Russian troops and held them there. At noon the enemy counterattacked in force, harrying the Uhlan3 Brigade in particular, which had been weakened by numerous postings. The 1st Battalion, assigned to the Chevauleger4 Brigade, was ordered to circle around to the northeast with the 6th Chevauleger Regiment and both cyclist companies to relieve the Uhlans and then carry the attack forward again, with elements of the Bavarian cavalry division on both flanks. The Battalion Staff, which had ridden ahead, were emerging from a small wood and making for some higher ground, when they suddenly came under brisk fire from that position. About 200 metres away, a long Russian line came into view. It appeared to have broken through a gap in the Uhlans’ weak, loosely spaced front line. The Staff galloped back into the wood. The only casualty was the battalion commander’s grey. It was bleeding from a bullet wound to the back, but it was not incapacitated so far. Despite heavy fire coming partly from the left flank, the 2nd and 3rd Companies, deployed up front with the Jäger, threw the advancing Russians out of all the occupied farmsteads in Puszkaryszki but came under increasing frontal and enfilade fire. Oberleutnant von Koerber (Ingo), with half of the 2nd Company, had reached the northern wood. He reported that from what he had seen of the ground, it should be possible and advantageous to encircle the Russian left flank. This officer had often proven himself to be reliable, and his recommendation was acted upon. At 5 in the afternoon another half-company and Hauptmann Müller’s Bavarian cyclist company were sent through the wood to outflank the Russians. Meanwhile, in the front line, the attack companies continued to work their way forward despite the Russian fire, with elements of the 4th Company reinforcing the left flank. They put in both a frontal and a flanking attack. The attack signal rang out across the whole battlefield. The Russians immediately began to give ground… Not until they had crossed the river Krozenta, which was deep in places, did Bonin’s battalion break off the pursuit. After marching 40 kilometres and taking Kielmy in a hard but victorious battle, they briefly went into rest.”

Eight days later, the Bavarian “Schwalangschär”1 and the horse artillery batteries returned the favour to their Prussian Guard comrades for their loyal assistance in battle. On 8 May the Bavarian cavalry division, which had ridden far ahead, suddenly fell back, and Bonin’s Battalion was in danger of being cut off by overwhelming Russian forces before it could reach the Niewjadza crossing.

The war diary reports: “Only the Chevauleger Brigade Staff with the 6th Chevauleger Regiment were still holding the bridge open on the east bank for Bonin’s reinforced battalion, which did not approach the bridge until around 7 in the evening. By that time, the first Russian shrapnel was already bursting over the crossing. Cossacks were attacking the rearguard of the 6th Chevaulegers on the east bank, but at the height of the crisis they bravely fought off the Cossack attack until the battalion, most of them running, had crossed the bridge.

The rearguard followed, but its rear element was attacked by Cossacks just before it got to the bridge. The brigade commander, Generalmajor Freiherr von Crailsheim, who was present, was seriously wounded by a lance thrust and died that evening in Beisagola. Once the Niewjadza crossing had been completed, pioneers set fire to the long wooden bridge.”

Only after an almost superhuman night march on very bad roads did the battalion reach the Bavarian cavalry corps, whose General had heroically sacrificed himself to save his Prussian comrades. Long after these eventful battles were over, the Prussian and Bavarian comrades would remember these combined arms exploits, which added a particularly glorious chapter to the history of the 5th Guard Regiment. On 5 October 1915, however, on the next page of his regiment’s war diary, Oberstleutnant von Radowitz wrote the following closing remarks: “So then, after 13 months of fighting in the East, the 5th Guard Regiment travelled by rail through the German homeland to the Western theatre of operations. The Officer Corps had to leave many dear comrades in the Polish and Russian soil, along with countless good grenadiers and fusiliers who had died like heroes. But everywhere the regiment fought – in East Prussia, in Southern Poland, at Ivangorod, at Lodz, on the river Rawka, in Masuria, from Przasnysz via Roshan to Olschany, in Kurland and at Wilna – it struck fear into the ranks of its enemies, brilliantly achieved the objectives it was assigned, and stitched everlasting glory onto its young Colours.”

When transferred back to the Western Front, the men of 5 G.R. spent time training for the challenges of the west. During the training they used Gew88 'commission rifles'. But as soon as their training concluded they were reissued Gew98 Mausers due to its superiority.

The Battle of the Somme

On 1 July 1916, a major Anglo-French offensive was launched towards Bapaume-Péronne, with the objective of relieving the French troops who were still holding out heroically in the terrible fighting at Verdun. That part of the German front line was only lightly defended, and at first it was pushed back. Then on 25 July, the 4th Guard Infantry Division was sent in to relieve the exhausted defenders. The Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest battles of the War, was to go on for months.

The events are described below in harrowing first-hand accounts from some of the combatants themselves. Leutnantvondem Knesebeck sets the scene.

“We spent the morning preparing ourselves mentally before going into action. Then the Regimental Commander spoke to us. He was serious, but full of confidence. Every man felt how he had grown alongside us. The afternoon was taken up with preparations for the march to the position. In addition to their usual equipment, which was heavy enough on its own, each man had to carry three days’ rations, three bottles of mineral water, two canteens of coffee, a sandbag containing hand grenades, and rifle ammunition. We also had to carry large pattern entrenching tools, flare pistols and flares.

The companies of the 1st and 2nd Battalions advanced at dusk and took their first casualties. The French pounded the regiment’s sector with heavy calibre artillery fire. We stumbled over the bodies of good German comrades. All the while we were concerned that the enemy might detect the relief operation in the bright light of their flares, which hung in the air for minutes at a time. Whenever a flare went up, everyone would lie on the ground, hold their breath and wait. The men we were relieving were all in a hurry to leave, glad to get out of the mess… Parts of the trench had been completely leveled by French trench mortars, and it was left unoccupied in places. There were no dugouts. The men lay under their shelter halves and slept as best they could, often alongside dead men killed in the previous days’ fighting.

A tunnel under the old Roman road to Amiens afforded some cover on the left flank. It led to the forward position of the 5th Guard Grenadier Regiment on our left, adjoining our own position. Although the tunnel was barely 20 metres long, it was constantly used to collect wounded men or men who had been buried by the barrage, who could not be evacuated to the rear by day. The worst of it was the many corpses lying around, covered in countless flies. No food tasted good in that foul air, and we were constantly tormented by a burning thirst… The men had to stay in their holes by day, lest they attract the attention of French aircraft and draw French artillery fire onto the sunken lanes.

This second regiment of the 5th Guard Infantry Brigade, formed at the same time, stood at the side of its sister regiment in nearly all the battles of the War.

The first aid post, on the lowest level, was always kept busy. The medical officers and their staff worked selflessly for hours, mostly under fire from the French, as the dressing station was simply a tent built into the escarpment. Long rows of wounded men lay outside it, awaiting their turn. The good stretcher bearers worked strenuously… The machine gun positions were dispersed across the whole sector. They were often buried by the barrage. The crews worked flat out to keep the guns ready to fire at all times. One evening at dusk, a man climbed out too soon and was spotted by aircraft overflying the sector, and the next day the deep hole was pulverised by heavy artillery. But the men managed to dig themselves out again, and they all survived with no worse than shock.

French aerial reconnaissance was far superior. Opposite the divisional sector alone were twenty or thirty tethered observation balloons observing every movement in the target area. During lulls in the fighting, the French would use low flying aircraft to adjust the fire of their heavy batteries, with tactical bomber squadrons(Kampfstaffeln)covering them from above. Other aircraft would machine-gun the shell holes and sunken lanes, wherever there were still signs of life. German aircraft could not compete with the numbers of the well equipped enemy air service…

Holding our position under heavy fire of all calibres, unable to defend ourselves, with an attack expected at any moment, put a great strain on the nerves. Flügelminen and rifle grenades would come whizzing over to us all morning. The Minenwere unnerving. They would tip over in the air and we could never tell where they were going to hit. They went off with a terrific bang. That went on for hours and drove many men half out of their wits. They would get Minen fever, seeing Minen where there were none, or sitting down and staring absently into the sky. The infernal concerto of artillery fire would always reach its climax late in the afternoon. In small company sectors, we counted over a thousand grenades and over a hundred Flügelminen every hour! Everything was shrouded in dust and smoke. It got so dark that we could no longer see a thing. Grenade fragments bounced off our steel helmets. The noise got on the nerves so much that some men went to sleep.”

Translator’s note: A Flügelmine was a type of trench mortar bomb with fins (or “vanes”). It was fired from a Flügelminenwerfer.

"The Flügelmine, thanks to its being guided by fins, had the advantage of not turning over but always hitting the target with the point, and boring into the ground. Thus it had a far greater effect on the surrounding area."

(Note: 5.G.R. Recieved their first batch of Steel Helmets on 22. July 1916)

Leutnant der Reserve Koßbach of the 7th Company adds to his comrade’s account, indicating the enormous numerical superiority of the Western powers over the German defensive front in terms of troops and materiel, already evident in 1916. He relates:

“On the morning of 30 July, the French opened up with Minen. When several machine guns joined in, it got uncomfortable. We no longer knew where to go. The men became nervous, especially when finally, around noon, the Minen alternated with heavy artillery fire on the trench. The sector had huge gaps in it. Most of my grenadiers crouched on the ground impassively, huddled around a traverse that was still standing.

The medical orderly shouted “Five men buried! We can still hear them!” His friend Peske was among them. He ran back again and started digging, shouting “Peske! My friend!” Other grenadiers helped him. An enemy aircraft spotted the commotion. Then came the “bang!” of artillery fire. Unteroffizier Soßnowski warned us that we would take more casualties. But we could still hear the buried men. So we had to try! Peske was dug out up to his lower body, but then the shelter took a hit and he found himself buried again up to his neck. I relieved the digging party, and the work continued. The enemy fire kept on coming. After several hours’ work, four men were free and were staggering around semi-conscious in what was left of the trench. The last man, Grenadier Palenberg, was dead by the time he was dug out. The men who had been buried along with him had still heard him praying. I wonder how many men died in these rabbit holes on the Somme…”

Such were the accounts of those who, as the Kaiser put it in his speech of 31 July 1916, “fought triumphantly against overwhelming odds” in the terrible battles of the second year of the War, and–at indescribable cost–defied all attempts by the enemy forces to break through into Germany. They would have to hold out for four more months against ever greater and stronger offensives made possible by inexhaustible supplies of materiel from North America.

All day and all night, week after week and month after month, the ill-fated frontline soldiers, the defenders of the German people, stood their ground between the artillery lines, defenceless in the Hades-like vacuum of their steel helmets, their nerves strained to the limit, expecting freshwaves of infantry attacks at any moment.

The enlisted men, some little more than boys, others older and bearded, closed ranks around their youthful leaders, high-spirited Guard Leutnants like von Maltzahn, von Bülow, von Wißmann, von Lenser, von Sittmann, von Koerber, von der Linde, Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach, Baron Henking, Rühe, von Liebermann, Graf Mellin, von dem Knesebeck, Roßbach, Kuntzen, von Hanstein, and the many other names that would appear again and again in the course of the war years, until one day they had to be marked with a black cross.

Countless times these trench officers, led into the great battles by outstanding generals and exemplary staff officers, provided the answer to the question from a pre-war poem, “Was will Majestätmit den Jungen?” (“What does Your Majesty wish from the lads?”)

“Despite his serious wound, the brave Leutnant der Reserve Kovats led hisfinemen forward in bounds, right through the thickest enemy fire.”

“Badly wounded, Leutnant der Reserve Schreib succumbed to his injuries.”

“Leutnant der Reserve von Koerber (Egbert), the commander of the 11th Company, popular and respected both as a soldier and as a man, was among those seriously wounded. His men carried him to the rear with care, hoping they might save his life. But to no avail. He went to a hero’s gravein the presence of his brother.”

So reads the War Diary, on page after page.

Yet the survivors of that most heroic epoch in German history became that “front generation”, tempered and welded together in the fire; men in their forties and fifties today, who carry deep in their hearts a vocation and a duty to confront and master the crucial challenges of the present day!

There were three brothers serving in the regiment. The eldest, Oberleutnant von Koerber (Wulfgar) had been killed while serving as a pilot in Serbia on 15 October 1915.

(Note: Oberleutnant Wulfgar von Koerber had transferred from 5GR to the Air Service and was a pilot with Feldflieger-Abteilung [Field Flying Detachment] 69 (formed in April 1915). He was killed on 15 October 1915 along with his observer and CO, Hauptmann Kurt Müller from Saxony, when their plane went down over Resiczabanya/Reschitza, now part of Romania.)

Winter 1917

The Spring Offensive - 1918

In the third year of the War, after the German front line on the Western Front had been shortened and moved back to the Siegfriedstellung, the regiment, as well as being involved in the heavy fighting at Arras, Méricourt and Lens, took part in the decisive “Autumn Battle in Flanders”. This would become the prelude to the “Great Battle in France”of Spring 1918.

“The companies are now down to around one-fifth of their strength”, reads the report of 4 October 1917, “the regiment’s hardest day of the War so far”. The commanders of the 4th, 6th and 7th Companies, the adjutant of the 1st Battalion, and many Unteroffiziere and Grenadiere died as heroes that day, and the commanders of the 2nd, 3rd and 11th Companies were wounded and taken prisoner. 419 men were reported missing. “The troops of the 4th Guard Infantry Division fought heroically under the most difficult conditions, in accordance with the old tradition of the Prussian Guard”, reads the final order of the general commanding, Graf zu Dohna, and the Commander in Chief, Feldmarschall Rupprecht von Bayern, Crown Prince of Bavaria, described the battlefield situation with the proud claim: “The Battle in Flanders is thus a heavy defeat for the enemy, but a great victory for us!”

The remainder of the “White Devils” had the difficult task of re-forming the regiment from the last home reserves [Heimatsreserven – home service reserves?], so as to be ready with their old striking force for the forthcoming Spring Offensive. Indeed, on 20 March 1918, the 5th Guard Regiment was once again ready for the attack! Oberst von Radowitz, their long-serving commander during the War years, having been appointed as commander of the 5th Guard Infantry Brigade, Major von Kriegsheim, every inch a soldier, led the regiment into the final and toughest decisive battles of the Great War.

The breakthrough between Gouzeaucourt and Bermand lasted only two days. The men from Spandau formed the front line. “Not a single man is missing!”, wrote Leutnant der Reserve Krüger. “Every man is eager to give the enemy the cold steel, at long last. Truly a shining symbol of the martial discipline and sense of duty of the Stormtroopers of the Spring of 1918!”

That martial discipline and sense of duty also sustained the surviving members of the youngest regiment of the Prussian Guard, right up to the hour of the tragic end of the War. As their fortunes worsened in the increasingly unequal and hopeless struggle against a world of enemies, the heroism of those front-line soldiers shone ever brighter! For wherever sectors of ground were lost in the face of overwhelming enemy numbers, they fell back with an exemplary defiance of death, took prisoners, captured materiel, and retook the old positions. To relate all the illustrious exploits performed by guardsmen of the Fifth amid the chaos of those turbulent final battles of the Great War would require a tome the size of the Nibelungenlied. It had long since become self-evident that a man would lay down his life for his comrades, as did the youthful Fähnrich von Falkenhayn at the Battle of Villers-Bretonneux. It was just as natural for individual survivors to keep fighting on their own. Men like the brave Grenadier Padowski who, as the last surviving member of his Stormtroop, went on to take 40 prisoners at Autheuil.

Soon the War Diary was only able to speak in terms of “remnants of the battalions”, reporting that this or that company had been disbanded. On 8 October, the Regimental Commander reported to Brigade that “though the combat value of the troops can generally be described as adequate, they have been much weakened, both physically and mentally, through constant deployment in the line”. Indeed, the daily toll of dead and wounded, ‘flu, stomach and intestinal sickness, malnutrition and increasing deficiencies in clothing, equipment and weaponry consumed their last reserves of strength. Nevertheless, the depleted regiment once again stood against the overwhelming enemy onslaughts in the bloody final battles of 13 October to 4 November. Even as the first dark shadows of revolution were looming on the horizon at home, and President Wilson, with his deceitful promises, was inciting the German people to be disloyal to their Kaiser, the hard-pressed heroes at the front went at the enemy with the same courage as they had on the first day of the War!

The last chapter of this regiment’s War Diary closes with a series of starkly worded final reports, out of which shine forth once again the greatness and the tragedy of the German soldiery of the War years: “11th and 12th Companies and a platoon from the 3rd M.G. Company wiped out after courageous resistance.” “10th Company now down to only six men.” “The Fusilier Battalion’s remaining reserve, a heavy machine gun, has just got into position.” “The remaining 135 men of the Fusilier Battalion have been organised into a tactical company”; and finally: “No more reserves available”…